If either skin undermining alone or subperiosteal undermining alone is performed, the surgeon can, to some extent, ignore the anatomy. These two planes of dissection are safe. Manipulation of the tissues between these two planes, however, necessitates an understanding of and constant attention to the anatomy to avoid complications.

There are five layers of critical anatomy: skin; subcutaneous fat; the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS)–muscle layer; a thin layer of transparent fascia; and the branches of the facial nerve (Fig. 49.2). These five layers are present in all areas of the face, forehead, and neck, but they vary in quality and thickness, depending on the anatomic area.

The first two layers, the skin and subcutaneous fat, are selfexplanatory. The third layer (SMAS) is the most heterogeneous (2). It is fibrous, muscular, or fatty, depending on the location in the face. The muscles of facial expression are part of the SMAS layer (e.g., frontalis, orbicularis oculi, zygomaticus major and minor, and platysma). In the temporal region, this layer is not muscular but is fascial in quality and is represented by the superficial temporal fascia (or temporoparietal) fascia.

FIGURE 49.2. The anatomic layers of the face. Although the quality of the layers differs in various areas of the face, the arrangement of layers is identical. The facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII) branches innervate their respective muscles via their deep surfaces.

The fourth layer consists of a layer of areolar tissue that is not impressive in thickness or strength, but is always present and is a key guide to the surgeon as to the location of the facial nerve branches. In the temporal area, this layer is known as the innominate or subgaleal fascia; in the cheek, it is the parotid– masseteric fascia; and in the neck, it is the superficial cervical fascia. Once under the SMAS, the facial nerve branches can be seen through this fourth layer. If the layer is kept intact, it serves as reinforcement to the surgeon that he or she is in the correct plane of dissection. If a nerve branch is encountered without this fascial covering, the surgeon must be aware that the dissection is too deep and nerve branches may have been transected. Just as it is convenient, but not totally accurate, to think of the galea–frontalis–temporoparietal fascia–SMAS– orbicularis oculi–platysma as a single layer, it is useful to think of the subgaleal fascia–innominate fascia–parotid/masseteric fascia–superficial cervical fascia as a single layer.

The fifth layer is the facial nerve, which is discussed in detail below.

If the surgeon remembers that the facial nerve branches innervate the respective facial muscles via their deep surfaces, the safe planes of dissection become obvious. Dissection in the subcutaneous plane, superficial to the SMAS–muscle layer, is safely performed anywhere in the face, whether it is the temporal region, cheek, or neck. Dissection deep to the SMAS, superficial to the facial nerve branches, requires care.

There are three to five frontal (or temporal) branches of the facial nerve that cross the zygomatic arch and innervate the frontalis muscle, orbicularis oculi, and corrugator muscles via their deep surfaces (3). Because the layers of anatomy, although present, are compressed over the arch, these branches are vulnerable to injury in this region. Dissection in this region can either be performed superficial to the nerve branches in the subcutaneous plane, or deep to the branches on the surface of the temporalis muscle fascia (deep temporal fascia) (4).

The zygomatic branches innervate the orbicularis oculi and zygomaticus muscles. One must remember that although the facial nerve branches travel deep to the SMAS layer, at some point these branches turn superficially to innervate the overlying muscles. Any dissection in the sub-SMAS plane in the cheek, whether as part of a composite rhytidectomy or standard dissection of the SMAS as a separate layer, necessitates a change of surgical planes at the zygomaticus major muscle to avoid transection of the branch to this muscle. The dissection plane changes from sub-SMAS to subcutaneous by passing over the superficial surface of the zygomaticus major and thereby preserving its innervation.

The buccal branches lie on the masseter muscle and are easily visualized through the parotid–masseteric fascia. Some buccal branches merge with branches of zygomatic origin to innervate the procerus muscle and provide additional innervation of the corrugator muscle. Consequently, the corrugator muscle receives innervation from the frontal, zygomatic, and buccal branches.

Earlier publications indicated that the marginal mandibular branches were located above the inferior border of the mandible in many cases. More recent studies demonstrate that, in fact, these branches are always located caudal to the inferior border of the mandible. The cervical branches innervate the platysma muscle.

Anatomic studies indicate that there are fewer crossover communications between the frontal branches and marginal mandibular branches, which helps to explain why injuries to these nerves are less likely to recover function in their respective muscles than injuries to the zygomatic or buccal branches.

In at least two areas of the face the anatomic layers are condensed and less mobile with respect to each other. These “ligaments” are areas where the skin and underlying tissues are relatively fixed to the bone (5). The zygomatic ligament (previously known as the McGregor patch) is located in the cheek, anterior and superior to the parotid gland and posteroinferior to the malar eminence. The mandibular ligament is located along the jaw line, near the chin, and forms the anterior border of the jowl.

The retaining ligaments restrain the facial skin against gravitational changes at these points. The descent of tissues adjacent to these points form characteristic aging changes such as the jowl. In addition, some surgeons feel that the ligaments must be released in order to redrape tissues distal to these points.

Although the platysma muscle is a component of the previously discussed SMAS/–muscle layer, it deserves special attention because of its clinical importance. The medial borders of the two muscles decussate to a variable degree in the midline of the neck, helping to explain the variability of aging patterns in the neck (6). The medial borders of the muscles tend to become redundant with age and contribute to the appearance of bands in the submental region.

The malar fat pad is part of the subcutaneous layer of the face. It is superficial to the SMAS layer represented in this region by the zygomaticus muscles. The malar fat pad appears to descend with age, leaving a hollow infraorbital region behind it and creating larger nasolabial folds and deeper nasolabial creases. Each of the major facelift techniques include a method to mobilize the malar fat pad and restore volume to the upper part of the face and malar region. As is discussed below, the extended SMAS technique involves mobilizing the malar pad in continuity with the SMAS layer. Other techniques involve mobilizing and repositioning the malar pad independent from the SMAS dissection.

The buccal fat pad is deep to the buccal branches of the facial nerve, anterior to the masseter muscle, and superficial to the buccinator muscle. Access to the buccal fat pad is achieved by performing a sub-SMAS dissection in the cheek and spreading it between the buccal branches of the facial nerve or through the mouth, by a stab wound in the buccinator muscle. Despite occasional indications to remove the fat pad in patients with very full faces, removal of cheek fat tends to ultimately make the patient look older. As a general rule, rejuvenation of the face involves redistribution, not removal, of fat.

The facelift operation inevitably disrupts branches of sensory nerves to the skin. Normal sensibility always returns eventually but numbness may persist for months postoperatively. The only named sensory nerve that is important to preserve is the great auricular nerve. With the head turned toward the contralateral side, the great auricular nerve crosses the superficial surface of the sternocleidomastoid muscle 6 to 7 cm below the external auditory meatus (7). At this point it is 0.5 to 1 cm posterior to the external jugular vein. The vein and nerve are deep to the SMAS–platysma layer, except where the terminal branches of the nerve pass superficially to provide sensibility to the skin of the earlobe. Transection of the great auricular nerve will result in permanent numbness of the lower half of the ear and may result in a troublesome neuroma.

The tear trough or nasojugal groove is an oblique indentation running inferiorly and laterally from the medial canthus. This groove is a subject of much attention at the present time. Although it is probably better included in a discussion of eyelid surgery, it deepens with age and is a frequent complaint of patients interested in facial aesthetic surgery (see Chapter 48). In general, facelift procedures do not address the tear trough. Redraping of orbital fat or microfat grafting is usually required.

The facelift procedure can be performed in the subcutaneous plane, the sub-SMAS (deep) plane, the subperiosteal plane, or a combination of the above. Each of the most commonly used techniques is described in the following sections.

The original facelift consisted of subcutaneous undermining only. The technique is still useful for an occasional patient, but more importantly, it is the basis for other techniques such as the SMAS technique, extended SMAS technique, and the SMASectomy–SMAS plication techniques.

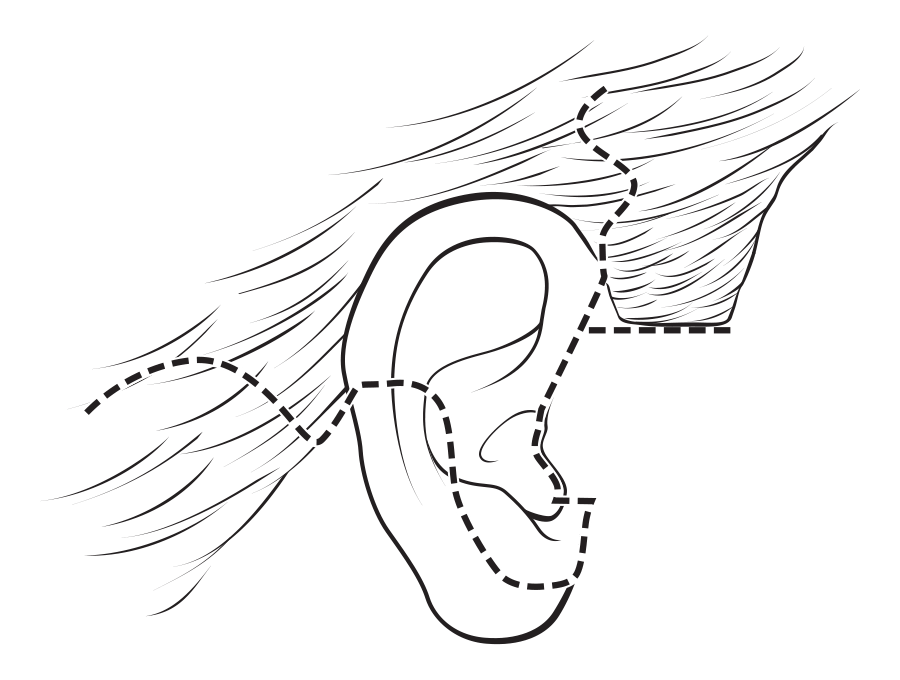

Incisions are designed to avoid distortion of the hairline and ear and to maximally disguise the final scars (Fig. 49.3). The goal is a scar that is so inconspicuous that one has to look for it. Although this is not always the case given the variable and unpredictable nature of wound healing, it is always the goal. If the patient has never had surgery before and has a normal hairline and sideburn, the incision is initiated within the hair, just above the ear. In patients with previous facelifts, the sideburn may already be significantly raised and posteriorly displaced, and an incision within the hair will result in further distortion of the sideburn. These patients are candidates for an incision along the anterior hairline. Patients with thin, sparse hair may be candidates for the hairline incision, even if it is the first procedure they have ever had. A transverse incision is also designed just below the sideburn to allow additional excision of cheek skin without raising the sideburn any higher than desired by the surgeon.

FIGURE 49.3. Standard facelift incision. Regardless of the technique chosen, some form of this incision is employed. In the temporal region the incision is shown within the hair. In patients with extremely thin hair, previous facelifts or if performing the minimal access cranial suspension (MACS) lift, the incision is made along the anterior sideburn and temporal hairline, rather than as shown here. In this illustration, the incision is shown along the posterior margin of the tragus. In men, and in women with oily or hairy preauricular skin, an incision in the preauricular crease may be preferable. In the short scar technique, the incision is terminated at the bottom of the earlobe or just behind it, and the entire retroauricular portion of the incision is eliminated.

The incision proceeds caudally along the junction of the ascending crus of the helix and the cheek. The eventual scar tends to migrate forward slightly and therefore should be placed 1 to 2 mm on the ear side of the ear–cheek junction. My preference is to make the incision in the same location in men. The incision is continued either at the posterior margin of the tragus (retrotragal) or in the pretragal region, usually in a natural skin crease. Patients, and many surgeons, erroneously believe that the incision along the posterior aspect of the tragus is always preferable. In fact, this incision frequently results in distortion of the tragus and is more likely a “tip-off” to a facelift than the preauricular incision. The novice surgeon is encouraged to perfect the pretragal incision prior to tackling retrotragal incisions.

When the retrotragal incision is made, the cheek skin is redraped over the tragus. The normal tragus is covered with thin, shiny, hairless skin (even in most men), and cheek skin is frequently not the ideal covering. I tend to use the retrotragal incisions in young women with thin, hairless cheek skin. In men, and in women with irregular pigmentation in the preauricular region, thick, oily cheek skin, or with furry cheeks, the incision is made in a preauricular crease. The key to an invisible scar is absolute lack of tension, not its location. If the retrotragal incision is chosen, the initial undermining is performed slowly and with care to avoid any damage to the tragal cartilage.

The incision passes beneath the earlobe and extends into the retroauricular sulcus. The incision is placed slightly up on the ear because it is also prone to migration and is best hidden if the final scar rests in the depth of the sulcus. The incision traverses the hairless skin in the retroauricular region at a point sufficiently high to be invisible if the patient were to have short hair or be wearing hair in ponytail. The incision then extends along the hairline for a short distance (1.5 cm) and passes back into the occipital scalp in the form of an “S” or an inverted “V.” When the neck skin is redraped, it is difficult to completely avoid a step-off in the hairline. If the incision extends too far down the hairline before passing into the scalp, this step-off, however small, is more noticeable. Hence the recommendation to limit the hairline portion to 1.5 cm.

Once the incisions are made, undermining is performed. The extent of undermining depends on the degree of aging changes, the area where these changes exist, the surgeon’s instinct about the health and vascularity of the tissues, and the manipulation planned for the deeper tissues. The various options for deeptissue manipulation are summarized below. Depending on the extent of undermining performed, a fiberoptic retractor may provide useful visualization. Many experienced surgeons undermine using a “blind” technique, gauging the depth of the dissection by feel and by watching the skin as the knife or scissors move beneath it. I prefer—and strongly recommend— that dissection be performed under direct vision. The tissues involved are thin and it only takes a minor slip of the scissor tip to cut a branch of the facial nerve and result in permanent disability for the patient. Some surgeons also find that countertraction applied by an assistant facilitates the dissection. The neophyte should be aware that the stronger the countertraction, the thinner the skin flap that is usually dissected. Although one wants to avoid dissection that is too deep, a flap that is too thin is also not desirable.

The undermined skin flap is redraped in a cephaloposterior direction. The transverse incision is made below the sideburn. The superior flap, with the sideburn on it, is fixed at the level of the ear–cheek junction—and no higher! The cheek skin is redraped along a line from the chin to the sideburn, overlapping the previously fixed flap. A triangle of hairless, excess cheek skin is excised and the cheek is fixed under some tension with a single suture at the top of the ear, in such a way that there is no dog-ear at the anterior end of the transverse incision. The neck skin is redraped more horizontally, parallel to the neck creases. A second suture is placed under some tension at the apex of the retroauricular incision. Care is taken not to redrape the transverse neck creases up on to the face. This creates another bizarre “facelift look.” Once these two tension-bearing sutures have been placed, the flap is incised so that the ear can barely be withdrawn from beneath the flap. The cheek flap is tucked up under the earlobe, leaving no possibility that the scar will be visible. The excess skin in front of and behind the ear is trimmed with extreme conservatism so that there is absolutely no tension on the closure. There should be almost no need for sutures because the coaptation of the skin edges is so precise. If a retrotragal incision is used, the tragal flap is cut so that it is redundant in all directions. The skin over the tragus tends to contract and, if there is not sufficient excess, will pull the tragus foreword, opening the view to the external auditory canal. A closed suction drain is left in the neck in the most dependent portion of the incision.

Regardless of the technique chosen for facelifting, the incisions and the final redraping are critical. If the incisions are performed properly, the redraping is appropriate, and the patient experiences uncomplicated wound healing, it is frequently difficult for the surgeon or the hairdresser to find the scars.

SMAS dissections vary in extent. The “traditional” SMAS dissection involves a transverse incision in the SMAS at a level just below the zygomatic arch and an intersecting preauricular SMAS incision that extends over the angle of the mandible and along the anterior border of the sternomastoid muscle. The SMAS is elevated off the parotid fascia, a separate anatomic structure, in continuity with the platysma muscle in the neck. The end point of the dissection is just beyond the anterior border of the parotid gland. The SMAS over the parotid gland is relatively immobile, compared to the SMAS beyond the gland. If dissection is not performed beyond the gland, insufficient release occurs, and tension on the SMAS is less efficiently transmitted to the jowls and neck. The SMAS–platysma flap is rotated in a cephaloposterior direction, trimmed, and sutured to the immobile SMAS along the original incision lines. The platysma portion of the flap is sutured to the tissues over the mastoid, increasing the definition of the mandibular angle.

The traditional SMAS dissection is effective for minimizing the jowls and highlighting the mandibular angle.

The extended SMAS dissection differs in two ways from the traditional SMAS dissection: the level of the transverse incision and the anterior extent of the dissection. The transverse incision is made above the zygomatic arch. Although concern has been expressed about the safety of this maneuver, it can be performed safely on a consistent basis with appropriate training. The same intersecting incision is made in the preauricular region and along the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The flap is elevated well beyond the anterior end of the parotid. The zygomaticus major is visualized. Dissection continues over the superficial surface of this muscle to avoid its denervation (Fig. 49.4). The large SMAS–platysma flap is rotated in a cephaloposterior direction, trimmed, and sutured along the original incision lines. The platysma is sutured to the mastoid periosteum.

The extended SMAS has the advantage of providing malar augmentation as well as an effect on the jowls and neck. It is my opinion, after performing this technique for many years, that there is a trade-off: the benefit of the high dissection is offset somewhat by a less-efficient effect on the jowls. The greater distance between the point of fixation and the jowls in the extended technique accounts for this difference.

FIGURE 49.4. Extended SMAS dissection. The SMAS flap is elevated, revealing the buccal branches of the facial nerve lying on the surface of the masseter muscle. The dissection passes over the superficial surface of the zygomaticus major, preserving its innervation.

Baker described the lateral SMASectomy procedure (8), and some variation of this technique is probably the most frequently performed facelift technique in the United States today. A strip of SMAS is excised on an oblique line between the angle of the mandible and lateral canthus (Fig. 49.5). The mobile SMAS is sutured to the immobile SMAS, accomplishing all the benefits of both the traditional and extended SMAS procedures. The platysma is sutured to the mastoid in a manner identical to a formal SMAS dissection.

In thin patients, the SMAS can be plicated along the same line, without removing any tissue. Although it may be necessary to remove a small amount of redundant SMAS over the angle of the mandible, the rest of the tissue is preserved. With the current trend of fat preservation, this is an appealing alternative. In heavier faces, the SMASectomy alternative is preferable.

The technique has enormous advantages. It is simple in design, can be modified to suit different facial shapes, and is less time-consuming than other techniques. It provides the malar augmentation of the extended SMAS with the more efficient effect on the jowls of the traditional SMAS procedure. It has the theoretical additional benefit that the SMAS is not undermined and thus not subject to the devascularization and atrophy that can occur when SMAS flaps are elevated. The disadvantage is that injury to buccal branches of the facial nerve can occur if sutures are placed too deeply.

FIGURE 49.5. SMASectomy. The oblique strip of SMAS to be excised is shown, extending from the angle of the mandible to the lateral canthal region. The platysma muscle in the neck is sutured to the mastoid periosteum. The mobile SMAS anterior to the SMASectomy is advanced to the immobile SMAS. This illustration shows the SMAS being advanced in an oblique cephaloposterior direction. In fact, the oblique SMASectomy defect can be closed in a vertical fashion (imagine the black arrows pointing vertically). The more vertical the closure, the greater the effect on the neck.

Hamra described the deep plane facelift that he modified to its current iteration, the composite rhytidectomy (9). This brief description does not do the technique justice, but does outline the key points. The SMAS and skin are dissected together as a single flap, rather than independently, as in the techniques described above. The benefit of the procedure is that theoretically the flap is better vascularized and less likely to slough. The technique, as Hamra performs it, includes a superomedial elevation of the malar tissues and orbicularis oculi muscle and a brow lift with a similar superomedial vector. The disadvantage of the technique is the magnitude of the procedure and the prolonged recovery period.

It is my opinion, never having performed this procedure myself, that the benefits of the procedure do not justify the invasiveness, risk, and prolonged recovery associated with the procedure.

The SMASectomy procedure, with its efficient elevation of the jowl and submental tissues, has decreased the need for submental incisions and open-neck procedures. As mentioned above, the closure of the SMAS (or the plication of the SMAS if no tissue is removed) is performed at a shorter distance from the jowls and submental region, and has a profound effect on those areas. There are, however, patients with enough redundant skin, excess fat, and redundant platysma who still require a formal submental dissection.

In these patients, an incision is made just caudal to the submental crease. Subcutaneous undermining is performed. A judgment is made about defatting of the platysma muscle, as mentioned below. An independent decision is made regarding removal of subplatysmal fat. The medial borders of the platysma muscle are plicated in the midline using buried interrupted sutures (Fig. 49.6). Compulsive attention to both hemostasis and perioperative blood pressure control is essential to prevent a hematoma when this larger dead space is created.

FIGURE 49.6. Treatment of medial platysma and platysma bands. Alternatives include (A) defatting of the anterior platysma without muscle modification; (B) midline platysmaplasty with wedge excision; and (C) resection of platysma bands without midline approximation. If a submental incision is elected, option (B) is usually the best alternative.

Feldman described the corset platysmaplasty. The medial borders of the platysma are plicated with a continuous monofilament suture that is run up and down the midline of the neck until the desired contour has been achieved. No manipulation of the lateral border of the platysma is performed.

I have had better experience with buried, interrupted sutures, which cause less bunching of the muscle. I also prefer to combine the midline platysmaplasty with lateral tightening of the platysma as described above under “SMAS Techniques” and “SMASectomy.”

A guiding principle is preservation of facial fat. This principle also applies to the neck but less so. Many patients benefit aesthetically from cervical defatting. The surgeon is meticulous about avoiding overdefatting because unsightly adhesions between the skin and platysma can occur. The same applies to removal of subplatysmal fat. Overskeletonization of the neck is one stigmata of an amateurish facelift.

The presence of large and/or ptotic submandibular glands prevents the creation of a clean neck after facelifting. The question of whether excision of the glands is worth the risk of bleeding and nerve injury has not been answered. Sullivan reports an acceptably low complication rate for submandibular gland resection associated with facelifting.

I have not had a complication from submandibular gland resection accompanying a facelift, but no longer believe that the benefits are worth the additional time required or the risk of bleeding and nerve injury.

Connell recommends shaving of the anterior belly of the digastric muscles to further define the cervicomental angle. I believe this creates an excessively sculpted, overdone look in many necks and is best avoided.

The single most powerful way to create a well-defined neck is to perform full-width transection of the platysma muscle across the neck (Fig. 49.7C). The muscle is divided under direct vision at least 6 cm below the inferior border of the mandible.

I only employ this technique in the most difficult necks, because irregularities and an overoperated look can be created and there is additional risk of hematoma and prolonged induration in the neck.

FIGURE 49.7. Lateral platysma modification. Alternatives include (A) advancement of lateral platysma parallel to mandibular border with suture fixation to the mastoid periosteum; (B) partial transection of lateral platysma with similar fixation; and (C) full-width transection of platysma with similar suture fixation. Most SMAS flap and SMASectomy/SMAS plication procedures include tightening of the lateral platysma. The most common alternative is (A). Alternative (B) may provide additional contouring to the mandibular angle in patients who require increased definition. Alternative (C) is the single most powerful technique to increase neck definition, but is associated with a higher incidence of neck irregularities, adhesions between the skin and muscle, and an overcorrected appearance in some patients.

Baker described the “short-scar” procedure, in which all the elements of the subcutaneous dissection with SMASectomy and lateral platysma tightening are performed, but the skin incision is limited to the preauricular portion. It is useful in younger patients with minimal excess neck skin. The incision is not extended beyond the earlobe, thereby avoiding the postauricular incision and the extension into the hairline. The technique relies on vertical redraping of the skin. Bunching of skin behind the earlobe often occurs but improves with time. Care is taken, however, to distribute the bunching as much as possible because patients will complain about it, even if it eventually improves. There is no question that the absence of the retroauricular incision is an advantage. While the retroauricular incision in most patients having traditional facelift incisions heals well and is sometimes virtually invisible, there are patients in whom this is not the case and the scar is visible, slightly hypertrophic, and, despite the surgeon’s best efforts, there is a slight step-off in the occipital hairline.

Tonnard described the minimal access cranial suspension (MACS) lift, which employs purse-string sutures in the SMAS structures and malar fat pad with vertical suspension (10). The vertical nature of the lift requires an incision along the anterior sideburn and anterior temporal hairline. The procedure can be performed in combination with midline platysmaplasty to improve the results in the neck. Excess skin may appear below the earlobe, which may require posterior cervicoplasty to correct.

Originally described by Tessier, Heinrichs has reported a large series of subperiosteal facelifts (11). The procedure is designed to rejuvenate the upper and middle thirds of the face. Subperiosteal undermining is performed through the following incisions in various combinations, depending on the surgeon: coronal incision or endobrow approach, subciliary incision, or an upper buccal sulcus incision. Hester has described a subperiosteal midface lift using endoscopic assistance through the lateral aspect of a lower-eyelid incision (12).

I am not impressed with the effectiveness or the longevity of subperiosteal lifts, but surgeons who have extensive experience with the technique probably have better results. Postoperative swelling can be profound after subperiosteal undermining. The author believes that the closer one is to that which is being lifted (i.e., the skin), the more effective the lift and considers subcutaneous undermining the gold standard.

The goals of secondary facelifting are to (a) relift the face and neck, (b) remove the primary facelift scars, and (c) preserve maximum temporal and sideburn hair. Dissection is usually easier than the primary dissection. Intraoperative bleeding and postoperative hematomas are also less frequent. The amount of skin excised at a secondary lift is much less than at the primary procedure. For this reason pre-excision of skin is never performed for a secondary facelift. The risk of nerve injury may be slightly higher in secondary facelifts, however. The first procedure may have distorted the anatomy and the tissues may be abnormally thin.

The shorter hairstyles of men are less forgiving than the longer hairstyles of women. Male faces tend to be larger and dissection is more time-consuming. Modified incisions have been described for men, but I use the same incision in patients of both sexes. Some men may have a tremendous amount of excess skin in the neck. When this is redraped into the retroauricular area, care is required to avoid a large step-off in the hairline. The previously reported higher incidence of hematomas in men than in women seems to be largely related to blood pressure. When blood pressure is controlled, the hematoma rates are very similar.

In an effort to make facelifting quicker and less invasive, several authors describe the use of barbed sutures in facelifting. The longevity of the result does not compare favorably with traditional methods. At the present time, the sutures are made of polypropylene and are permanent. Concerns have been raised regarding the safety of permanent barbed sutures in the subcutaneous position. Long-term data are not yet available.

Dr. Thorne is the Editor-in-Chief and the author of several chapters in Grabb and Smith's PLASTIC SURGERY, 7th Edition.